![]() Click on the headings to open them. They will open on this page. Open the following link

for further

information about these headings if required.

Click on the headings to open them. They will open on this page. Open the following link

for further

information about these headings if required.

Your browser does not support these headings. To ensure that the contents remain accessible, they have been automatically opened so that all the information on the page is displayed.

However, to take advantage of the headings and to ensure that the layout and design of this site are displayed correctly, you are recommended to upgrade to a current version of one of the following standards compliant browsers:

- Internet Explorer (http://www.microsoft.com/ windows/ie/downloads/ default.mspx)

- Mozilla Firefox (http://www.mozilla.org/ products/firefox/)

- Opera (http://www.opera.com/download/)

There are references to sources and further reading within the text. You can view the full reference by clicking on the name to open a 'pop-up window'. You can then add comments to these references and include them in a personal references list.

Ongoing instructions are provided, but if you would like to read more information on how to do this before you begin, or if you experience problems, select this link for instructions on how to use the personal references list

Instructions:

- Select the references to see full bibliographic details in a pop-up window.

- NB. If you use pop-up window blocking software, you will need to deactivate it for pop-ups on this site to use the reference list. Alternatively, all full references can be seen by navigating to the 'References' page.

- If you would like to add a comment to attach to your record of the reference, write in the text box.

- Select 'add to list' to add the reference and comment to your list.

- You can view your references at any time, by selecting one of the 'Show references list' links. This will open your list in a pop-up window.

- NB. Each module has a different reference list. If you are navigating between modules, any references collected will be saved to different lists. To view the list for a particular module, select any 'Show references list' link within that module.

- If you leave this page, your list will be saved and will be

available for you to refer to again if you return.

(This will not work if you have disabled cookies in your browser settings) - NB. Comments will not be saved if you navigate away from the page. You should copy all comments before you leave if you would like to save them.

- Use of the references list is JavaScript dependent. If JavaScript is disabled, it will be necessary to open the 'References' page to view the full references.

Glossary links are also included within the text. If a word appears as a link, clicking on this link will show the definition of the word in a 'pop-up window'. Select the following link for information about these glossary links if required.

- Select the links see the definitions in a pop-up window.

- NB. If you use pop-up window blocking software, you will need to deactivate it for pop-ups on this site to use the glossary links. Alternatively, all glossary definitions can be seen on the 'Glossary' page in the 'Resources' section.

- Use of the glossary links is JavaScript dependent. If JavaScript is disabled, it will be necessary to open the 'Glossary' page to view the definitions. Opening this page in a new window may allow you to refer more easily to the definitions while you navigate the site.

Introduction

Introduction

Online interviews are increasingly used as a data collection method by social scientists. There are numerous examples of research which has used email interviews (Illingworth 2001; Bampton and Cowton 2002; Kivits 2004; Kivits 2005; James 2007) but until relatively recently, few which focus on the use of synchronous interviews (Coomber 1997; O'Connor and Madge 2001; Stieger and Goritz 2006; Fox et. al 2008; Ayling and Mewse 2009).

Asynchronous

v synchronous interviews

Asynchronous

v synchronous interviews

Online interviews can be broadly divided into two main types: Synchronous and asynchronous.

Synchronous online interviews are those which most closely resemble a traditional research interview in that they take place in 'real time' in an environment such as an internet chat room. All participants must be online simultaneously and questions and answers are posted in a way which mimics a traditional interview. This is the type of online interview which has received the least academic attention to date.

By contrast, asynchronous interviews take place in non-real time, for example using email. An asynchronous interview will usually involve the interviewer emailing interview questions to respondents to answer at their own convenience. Neither party needs to be online at the same time. Asynchronous interviews are usually facilitated by email (Murray and Sixsmith 1998; Selwyn and Robson 1998; Kivits 2004; Kivits 2005; James 2007), discussion board services (also known as bulletin boards, discussion groups or web/internet forums) (Ward 1999; Im and Chee, 2006) or in a mailing list or listserv environment. (Gaiser 1997).

Asynchronous

interviews: Email

Asynchronous

interviews: Email

Interviews conducted through the use of email have been one of the most widely used internet-mediated methodologies to date (see for example, Mann and Stewart 2000; Illingworth 2001;Kivits 2004; Kivits 2005; James 2007; Bampton and Cowton 2002; Walther and D'Addario 2001).

The format of an email interview is that the researcher, having obtained email addresses and agreed participation from all respondents, sends out an email which contains the interview questions either in the body of the email or as a word attachment to the email. The participant responds to the interview questions, either in the body of the email or in a word document and returns the completed answers to the researcher. Often the interview will take place over a period of time and questions are sent in stages so that the interviewee is not overwhelmed with a long list of questions at the start of the process.

Some of the advantages of email interviewing are as follows:

- Email is perhaps one of the most familiar modes of online interaction and one of the easiest to set up in terms of technological requirements (O' Connor et. al., 2008);

- Interviewees can answer the interview questions at their convenience. There is no time restriction. This can be particularly valuable when participants are located in different time zones;

- Both the interviewer and interviewee have time to consider their questions and answers, allowing for a process of drafting, redrafting and editing, and allowing for deeper reflection;

- The time delay between responses may also increase scope for flexibility as the interview develops, allowing for greater ownership in the research process by participants who may respond to questions in unexpected ways and directions, allowing the interviewer scope for further reflection and, as appropriate, for variation from pre-constructed interview scripts in response to their choices (James 2007).

- The time-scales of email interviews, which often involve repeated emails over a relatively long period, may make it particularly appropriate for longitudinal research;

- Email can also be used to construct an 'almost instantaneous dialogue between researcher and subject … if desired' (Selwyn and Robson 1998, 2);

- Both the interviewer and interviewee have time to consider their questions and answers.

On the other hand, however, many of these advantages also come with potential disadvantages. The relative simplicity of email interviews from a technical standpoint must be balanced with the ease with which participants can delete or ignore emails. The potential advantages brought by the lack of time restriction and the slowing down of the communication process may also lead to problems concerning lack of engagement or to the production of 'socially desirable' answers rather than the more spontaneous responses typical of synchronous interviews (both online and face-to-face) (Joinson, 2005). The scope for increased flexibility, reflexivity and participant ownership in how the interview develops must also be balanced against the fact that delayed interaction and the inability to spontaneously direct the flow of conversation, and prompt and probe participants may lead to a paucity of data compared to synchronous interviews (Sanders, 2005).

Asynchronous

focus groups

Asynchronous

focus groups

Email can also be used to conduct asynchronous focus groups by encouraging the group to use the copy-to-all function when responding to questions. As this depends on each individual remembering to use this function, however, the use of a mailing list environment which manages the process of disseminating individuals' emails to all the members of a mailing list group is likely to be more effective (Hewson, 2007). Gaiser's (1997) online focus groups were conducted in in such an environment, using listserv, which is one of the key software applications for managing mailing lists. One advantage of this is that all participants are regular listserv users and have a high degree of familiarity with the technology. It also eliminates the need to set up mutually convenient chat times. However, it is not a real time facility, respondents can post their reply at anytime and as such the facilitator cannot always play an active role in moderating the interview. Thus, compared to synchronous interviews, the level of group interaction is reduced and the sense of immediacy removed. However, the fact that the researcher cannot always be available to moderate the discussion can lead to a relatively high level of group independence and self-management. This can be 'threatening and difficult to manage' for the researcher and can have mixed results, leading at times to the collection of rich, unexpected, participant-driven data, or to unfocused, off-topic exchanges (Gaiser, 2008). As Gaiser (2008:299) states, 'part of the moderator's task ... is to determine an acceptable level of self-management and then to get comfortable with its application'. By nature, this type of interaction is also less private than an individual email interview as interviewee responses to questions can be seen by all list users. Discussion boards can also be used to manage focus group interviews in a similar way. Ward (1999) posted her interview questions periodically on a well-used bulletin board and users posted their responses to the same bulletin board. Here, again, the responses are seen by all of the bulletin board users and as such respondents are likely to be less candid than they would be in a private email, though this must be balanced with the fact that online discussion groups may provide a more comfortable space to explore sensitive issues than face-to-face focus groups (Im and Chee, 2006). As with mailing lists, this type of interview facilitation can be useful in generating lively discussions between the respondents and allowing for explicit exploration of interaction and meaning within the social context of a group (Watson et.al., 2006), but moderating the group asynchronously can have implications around power and control that must be considered.

Synchronous

online interviews

Synchronous

online interviews

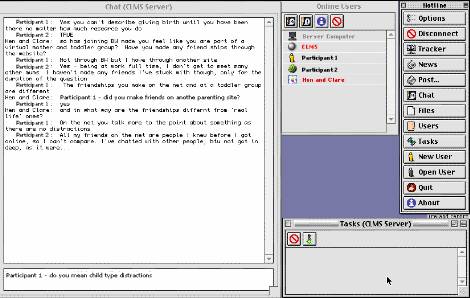

While the body of literature on asynchronous online interviews has grown substantially, that focusing on synchronous online interviewing has been slower to develop (O' Connor et. al. 2008), and there has been relatively little exploration of the reflexive experiences of researchers, particularly those conducting synchronous interviews (Fox et. al., 2008). Empirical studies involving text-based interviews include the work of Gaiser (1997), Smith (1998), Mann and Stewart (2000) Chen and Hinton (1999), O'Connor and Madge (2001), Stieger and Goritz (2006) and Fox et. al., (2008). As Chen and Hinton (1999) have observed, 'real time' online interviews provide greater spontaneity than online asynchronous interviews, enabling respondents to answer immediately and interact with one another. They are easier to control and manage in real-time by the researcher, reflecting more traditional face-to-face groups (Gaiser, 2008), though, in terms of technology, they can be more complicated to set up than asynchronous interviews. This is because at the design stage the researcher must select an appropriate software package to facilitate the interview. Perhaps the most widely used approach to online synchronous interviews has been facilitation through conferencing software (Mann and Stewart 2000; O'Connor and Madge 2001). Both Stewart et al. (1998) and O'Connor and Madge (2001) utilised conferencing software packages which were being used for teaching purposes in their own university departments. Access to the software was arranged by the researchers and downloaded by the participants. These software packages have the facility for both synchronous and asynchronous chat. The synchronous chat is facilitated in a chat-room type environment. Figure 1 illustrates the virtual interface as seen by participants. The screen consists of a number of different windows and a tool bar. There is a large 'chat' window in which the dialogue is displayed, beneath this is a smaller window where users type their text, and press return, seconds later the contribution is displayed, prefixed with their name.

Figure

1

Figure

1

![]() Select the image to see a larger version with a description.

This link will open in a new window which you should close

to return to this page.

Select the image to see a larger version with a description.

This link will open in a new window which you should close

to return to this page.

Similarly, Fox et. al., (2008) used a synchronous online chat facility set up and hosted within their university with password-protected access for moderators and participants who were young people, while Stieger and Goritz (2006) utilised an online Instant Messaging service to carry out their online interviews.

Researchers who have used synchronous chat in this way have reported on a number of differences between this approach to interviewing compared to a more traditional approach. In particular, interview design, building rapport and the virtual venue are issues which the online interviewer must consider (see 'Advantages and disadvantages' and 'Designing online interviews' sections for further details). For example, in the disembodied interview all the subtle visual, non-verbal cues which can help to contextualise the interviewee in a face-to-face scenario are lost. This represents an immense challenge to the researcher, given that the traditional textbook guides to interviewing rely heavily on the use of visual and physical cues and pointers in order to build rapport and gain the trust of the interviewee. It is, therefore, important to seek alternative ways of creating a relaxed environment and building a sense of rapport with respondents. The use of photographs posted on webpages or a high level of self-disclosure at an early stage of the interview can be helpful (see O'Connor and Madge, 2001 for a more detailed discussion).

OPEN MY REFERENCE LIST ADD ALL REFERENCES « BACK UP NEXT »